El Tableau Économique de Quesnay

Quesnay (1766). : "Analyse de la formule arithmétique du Tableau Économique de la distribution des dépenses annuelles d'une Nation agricole" En : Journal de l'agriculture, du commerce & des finances; (juin 1766 : 11-41) ; tome II ; 3ème partie. En : http://www.taieb.net/auteurs/Quesnay/t1766.html

El Tableau économique de Quesnay, la obra fundacional de la fisiocracia, ofrece un visión de la economía, prácticamente, como parasitaria de la agricultura, en la cual el agricultor es el único elemento productivo de la sociedad y el terrateniente es el articulador de la economía al monopolizar todo el producto neto (curiosamente, el peso de la economía productiva – creación de producto neto – no recae sobre las manos que trabajan la tierra, ya que los jornaleros agrícolas también son consumidores improductivos, "parasitarios", sino en el agricultor: que puede ser libre, pero como prototipo es el colono arrendatario de la tierra que realiza y coordina – a los jornaleros para – la producción agrícola).

Es una obra que plasma una importantísima labor de teorización y abstracción económica que la convierte, a pesar de su simplicidad, errores y contradicciones, en el tratado económico pre-clásico más influyente de la historia, cuya presencia sobrevivió a la moda fisiócrata para proyectarse hasta el siglo XX.

"Quesnay y représente l'économie comme un domaine cohérent de nature systémique en s'inspirant de la découverte, réalisée un siècle et demi plus tôt par William Harvey, du mécanisme de la petite et de la grande circulation sanguine.” [En página web] Esta es una afirmación interesante, ya que sitúa su obra económica dentro de un pensamiento mucho más amplio – conviene recordar que Quesnay era médico y cirujano –, influido por la revolución científica.

La novelesca trayectoria vital del polifacético economista francés le llevó a publicar su obra más famosa en los talleres reales de Versalles en 1758, a sus 64 años. “Au total, Quesnay en rédigera trois versions [de su obra]. La première édition date de novembre ou décembre 1758. Cette première version du «zigzag» est basée sur un revenu de 400 livres et comportait vingt-deux Remarques. La deuxième édition, qui date du printemps 1759, part d'un revenu de 600 livres et 23 remarques. La troisième édition, parue en 1759, est également basée sur un revenu de 600 livres et est suivie d'une «explication» de douze pages et d'un «extrait» comportant vingt-quatre maximes. ” [En página web]

La obra de Quesnay fue considerado por sus propios seguidores como el invento más importante de la historia, junto a la escritura y el dinero. Para Mirabeau era el “…gran descubrimiento de nuestra época, pero cuyos beneficios recogerá la posteridad” [Ver pág A, pág B]

Adam Smith escribió, en 1776, que el sistema que define el Tableau “…es acaso el que más se aproxima a la verdad de todos cuanto se han publicado hasta ahora…”. Mientras que Marx, a la vez que criticaba los errores y las contradicciones internas del libro, lo calificaba de primera concepción sistemática de la producción capitalista, y expresó, en la Historia Crítica de las Teorías de la Plusvalía, que “Jamás la economía política había concebido una idea tan genial”. [Ver pág C, pág D]

“El objetivo central del “Tableau Economique” fue realizar un análisis de la economía de Francia como un todo y mostrar cómo surgía el excedente económico y cómo circulaba entre las diferentes clases de la sociedad. El “Tableau” fue el primer intento en la historia de analizar una economía como un sistema de relaciones entre sus diversos sectores o clases, pero además es considerado como el mojón que anuncia la etapa de nacimiento de la economía como disciplina científica autónoma.” [En página web]

Dicha obra “...es una representación gráfica de la circulación de riqueza entre las clases sociales en que dividieron la sociedad de acuerdo con el criterio de «productividad».... Supone una clara conciencia de la interdependencia económica y se adelanta a las teorías del equilibrio general del s. XIX" y es el ancestro de los sistemas de Input-output multisectoriales (tablas de entrada-salida) [en página web] de Marx, Sraffa y, más recientemente, de Wassily Leontief, Premio Nóbel de Economía de 1973, quien reconoció la influencia de Quesnay en su obra al expresar que su libro La Estructura de la Economía Americana podía definirse como un intento de construir “…un Tableau Economique para Estados Unidos…”.[Ver pág E, pág F]

Funcionamiento del Tableau Économique

Los fisiócratas han presentado dos versiones del Tableau: el zigzag o circulatorio del producto neto y el Tableau Économique general que representa la circulación de la reproducción total. Quesnay también enunció una teoría del capital bastante completa.

Un resumen en Francés del funcionamiento del Tableau économique está disponible en http://fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/Quesnay . Un resumen en castellano, muy sucinto, es el siguiente: “La reproducción total alcanza cinco millones. De éstos, dos millones los conserva la clase productiva para semillas, autoconsumo y beneficio normal del agricultor. Dos millones los recibe la clase propietaria en forma de renta, diezmo e impuestos, y un millón más va a parar a la clase estéril en pago de artículos manufacturados. Los propietarios gastan los dos millones, mitad en artículos manufacturados y mitad en compra de subsistencias. De este modo, se restituyen los 5 millones en la agricultura, restableciéndose el equilibrio.” [ver página web]

(1) the proprietary class (landlords)

The model in our example involves two goods, grains and crafts. Grains are produced with land, labor and capital (meaning here livestock and seed). The production of crafts require local grains and imported foreign goods as raw materials. The following five protagonists are involved:

Farmer: 150 grain + 150 crafts

The landlord, of course, has the most sumptuous lifestyle. The merchant, being a foreigner, is only passing through, so he needs no local sustenance.

Quesnay (1759, 1766a, 1766b) used the term "advances" to denote capital, i.e. expenditures during a production process that are drawn from a previously-accumulated fund. He identified four types of capital depending on the sort of expenditures they were earmarked for.

(1) avances foncières (fundamental/landed advances): one-time capital expenditures undertaken by landlords on their land, e.g. land-clearing, drainage, fence-building, etc.

(2) avances souveraines (sovereign advances): one-time capital expenditures undertaken by government, e.g. roads, bridges, etc.

(3) avances primitives (primitive advances): expenditures on durable producers' goods, e.g. horses, cattle, ploughs, etc. In the Tableau, these are also referred to as avances originelles (original advances).

(4) avances annuelles (annual advances): expenditures on the wages of labor and non-durable producers' goods, e.g. cattle-feed, seed, etc.

In our example, we shall ignore all forms of capital but the fourth, the avances annuelles. We have two production processes -- grains and crafts -- and both of them needs to use previously-accumulated stocks of grains as raw materials.

To produce 1500 units of grain, the Farmer needs 300 units of grain to sow his field and feed his cattle. But he also needs to keep himself and his laborer alive during the course of the year. So, every year, he will retain 300 units of grain, 150 for himself and 150 for his laborer. Of course, both the Farmer and the Laborer have other needs, e.g. clothes, furniture etc. These crafts must be bought on the market with cash, but the Farmer can only acquire cash by selling his grain on the market. Thus, we shall assume that after the sale of the grain, the Farmer keeps $300 cash to pay for crafts -- $150 for himself and $150 for the Laborer. Thus, the Laborer's full wage in the course of the entire year is 150 grain + $150 cash. The Farmer's expenditure on himself is also 150 grain + $150 cash.

So, let us examine the expenditures and receipts of the Farmer. He produces 1500 units of grain, retains 600 units for internal use (avances annuelles = seed, cattle-feed, food for himself and Laborer) and places the remaining 900 units of grain on the market. The 900 grains converts into $900 cash on the market, of which $300 will be taken to buy crafts for himself and his Laborer, thereby leaving 600 left over. This $600 is the net product.

Let us now turn to the Artisan. To produce 750 units of crafts, he needs 300 units of grain as raw material and $150-worth of foreign inputs (e.g. imported cloth, etc.) He needs to buy both of these with cash -- the grain on the local grain market, the foreign inputs from the foreign merchant. But the Artisan also needs to live during the year. We shall assume he has the same consumption needs as the Farmer and the Laborer, i.e. 150 crafts + 150 grain. He can produce the crafts for himself (i.e. he retains 150 units of crafts for own-consumption), but the 150 grain needs to be acquired on the market. So, every year, the Artisan needs to buy a total of 450 units of grain on the market and $150-worth of inputs from the foreign merchant. Consequently he needs $600 in cash, which he must acquire by selling 600 units of crafts on the market. As his total output (750 crafts) is equal to his total expenditures (750 = 150 crafts + $600 cash), then the artisan produces no net product.

Now, let us turn to the proprietor class. The Landlord's sumptuous lifestyle requires 300 grains + 300 crafts which must be bought on the market. He thus has a need for $600 cash. He acquires this by charging the Farmer $600 rent for the year. Notice that, with his rent, the Landlord has just expropriated the entire net product of the Farmer.

The Merchant is the only loose end. We will just suppose that he brings $150-worth of foreign inputs (which he sells to the artisan) and then turns around and uses the cash to buy 150 units of local grain for export.

Production of grain requires inputs of labor, land and livestockProduction of crafts requires grain and foreign inputs as raw materials. "Livestock" means both animal capital and seed capital.

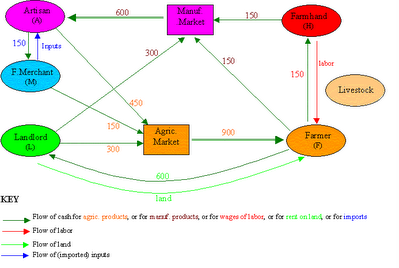

[MODELO CIRCULAR]

Only Farmer and Artisan produce. Some of their produce they retain internally, the rest they supply to market. What is supplied to market is exchanged for cash; what is retained internally does not command cash. At the market, their goods are bought up by different people.

In the following account, we trace the movement of grains and crafts. Note that that these numbers are not payments but merely how the actual output flows. Here is the account:

Agricultural Sector: (output owned by Farmer)

Produces 1500 grain = 600 internal + 900 to market.

Of which:

Internal = 600 = 300 to Livestock + 150 to Laborer + 150 to Farmer.

To Market = 900 = 300 to Landlord + 450 to Artisan + 150 to Merchant

Manufacturing Sector: (output owned by Artisan)

Produces 750 crafts = 150 internal + 600 to market.

Of which:

Internal = 150 for Artisan

To Market = 600 = 150 to Farmer + 150 to Laborer + 300 to Landlord

Notes: In the agricultural sector the Farmer has to use part of his output to feed his livestock, a new category. Note also that the Merchant does not buy any of the Artisan's goods, but only the Farmer's grain. The Laborer is to receive 150 of the Farmer's output. This is only part of his wage (paid in kind). Another part will be paid in cash (as we shall see). The 300 units of grain going to the Landlord are not rent payments -- the Landlord just happens to buy the Farmer's grain on the market place.

Production Flows. The production story is captured in the flow diagram 1 below.

Let us now turn to tracing the cash flow. Cash is exchanged for the goods on the market -- i.e. for agricultural goods and manufactured goods. We have not mentioned factors of production and their payment yet. So, we must now put them in place. There are three factors which trade for "cash": the labor of the farmhand (used by farmer and for which a cash wage is paid), the land of the landlord (used by farmer, and for which a cash rent is paid), and finally imported inputs from the foreign merchant (used by the artisan, which must be paid in cash). So, cash trades against both commodities and factors.

Farmer:

Receives $900 from selling grain in the market (see above)

Then:

Pays himself 150 units of grain.

Pays Laborer $150 in cash, 150 in grain.

Pays Landlord $600 in cash (for rent)

Pays Artisan $150 in cash (for crafts)

Thus: Farmer gets $900 in cash and spends $900 in cash.

Landlord:

Receives $600 in cash from Farmer as rent payment

Then:

Pays Farmer $300 in cash (for grain)

Pays Artisan $300 in cash (for crafts)

So gets $ 600 in cash and pays spends $ 600 in cash.

Artisan:

Receives $600 in cash from selling crafts in the market (see above)

Then:

Pays $300 in cash to Farmer (for grain to be used as raw materials)

Pays $150 in cash to Farmer (for grain for own consumption)

Pays $150 in cash to Merchant (for imported inputs)

So gets $600 in cash and pays spends $600 in cash. Notice that the 300 grains he gets as raw materials is lost to the economy (perhaps he makes baskets out of livre notes!)

Farmhand:

Receives $150 in cash from Farmer (wage paid-in-cash) + 150 in grain from Farmer (wage paid-in-kind)

Then:

Pays $150 in cash to Artisan (for crafts)

So gets $150 in cash and pays $150 in cash.

Foreign Merchant:

Receives $150 in cash from Artisan (for imported inputs)

Then:

Pays $150 in cash to Farmer (for grain)

So gets $150 in cash and pays $150 in cash.

[MODELO ZIG-ZAG]

The zig-zag is effectively the flow of funds in a dynamic form rather than the "static" natural state. The left side of the Tableau represents the productive class (farmer) and the right side represents the sterile class (artisan). At the top in the center is the landlord. The landlord begins the flow by buying goods from both the artisan hence the income flows from the landlord to both the left (productive) and right (sterile) columns.

The income received from the landlord is registered by theclasses in their respective columns. Note that, from theincome, there is an arrow that indicates "expenditures" whichthen extends across the Tableau to the other column. Theseexpenditures are that of the farmer for crafts and the artisanfor grain - thus they cross each other to become the incomeof the artisan and the farmer respectively. The farmer and theartisan then use this new income again to buy goods from each other - thus they cross again. That then becomes subsequent income and thus cross-expenditure. Thus, the zig-zag across the columns is the income-expenditure process of the farmer and the artisan.

Notice that the landlord's initial expenditure is in fact equal to his total rent income of 600. So, rent "initiates" the process. As the zig-zag diagram and our previous numerical example shows, from his 600 rent income, the landlord spends 300 on agricultural products (to the left column in the Tableau) and 300 on manufactured products (on the right column). In the second line of the Tableau, from the Farmer's income of 300, he spends 150 on manufactured goods (thus retaining 150 for paying the farmhand for his labor), while from the Artisan's initial inome of 300, he spends 150 on agricultural goods (thus retaining 150 for imported inputs -- notice the Artisan's propensity to import is different from our earlier numerical example). From the subsequent 150 income generated for each class, a new round of expenditures for grains and crafts occurs (75 to each), etc. This income-expenditure process is a convergent series. The bottom of the column depicts the "natural state" once all the flows have been worked out. Note that along the farmer's column on the left side, there is a small arrow indicating the "creation" of produit net by the farmer at every stage in the process. This is summed at the bottom as the total net product of the economy. Notice that it is 600 -- which is identical to the landlord's "initial" expenditure from rent. Thus, the "rent on land" and the "net product" created are the same.

0 Comments:

Publicar un comentario

<< Home