Sistemas-Mundo y España

para ver el gráfico: pinchar en él, y luego cuando se abra la ventana nueva, pinchar en la esquina inferior derecha.

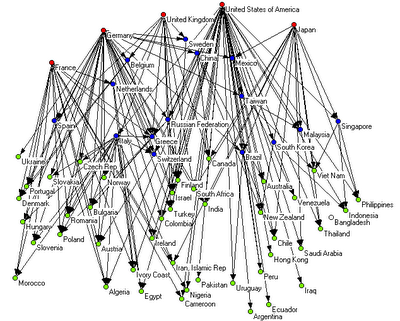

para ver el gráfico: pinchar en él, y luego cuando se abra la ventana nueva, pinchar en la esquina inferior derecha.Como simple curiosidad, me gustaría destacar un gráfico de V. Paina sobre la jerarquía comercial en el mundo, realizada aplicando las ideas de Wallerstein y de la Teoría de Sistemas-Mundo. El estudio incluye 64 países, y produce conclusiones típicas de esta escuela que resultan peculiares por el alto nivel de complejidad matemátizante de los métodos utilizados.

En la gráfica se distinguen en rojo los países del centro, en azul los de la semi-periferia y en verde los de la periferia. Las flechas señalan los vínculos de dominación de unos sobre otros. Supongo que la posición vertical simboliza la posición de un país en el “balance de fuerzas”: mientras más arriba, más dominante.

Resulta interesante - y peculiar - notar el papel que se le otorga a España, y su posición vertical en relación con los demás países, como México, Holanda, Rusia, Italia, Malasia, Singapur o Suecia , y los vínculos de dominación que se le atribuye sobre Polonia y Algeria (!?). Asimismo, España ocupa la décima posición en el índice de fuerza entre los 64 países estudiados.

(Ver también la posición de Argentina en el gráfico)

Strength Index

Country (Strength Index)

United States of America (363)

Germany (355)

France (206)

Italy (203)

United Kingdom (201)

Japan (190)

China (119)

Netherlands (117)

Russian Federation (64)

Spain (62 )

[ Ver: Piana, Valentino (2004).: Hierarchy Structures in World Trade. Economice Web Institute. En:

http://www.economicswebinstitute.org/essays/tradehierarchy.htm ]

Wallerstein

Wallerstein, por sus criticas contra el capitalismo y su postura a favor de los paises “periféricos”, es uno de los ídolos del movimiento anti-globalización.

En la siguiente cita de Wallerstein, sobre el desarrollo de la economía desde la Edad Moderna, se puede notar el tono y el lenguaje cargado de adjetivos que recuerdan a las obras divulgativas de Noam Chomsky.

“In the sixteenth century, Europe was like a bucking bronco. The attempt of some groups to establish a world-economy based on a particular division of labor, to create national states in the core areas as politico-economic guarantors of this system, and to get the workers to pay not only the profits but the costs of maintaining the system was not easy. It was to Europe's credit that it was done, since without the thrust of the sixteenth century the modern world would not have been born and, for all its cruelties, it is better that it was born than that it had not been.

It is also to Europe's credit that it was not easy, and particularly that it was not easy because the people who paid the short-run costs screamed lustily at the unfairness of it all. The peasants and workers in Poland and England and Brazil and Mexico were all rambunctious in their various ways. As R. H. Tawney says of the agrarian disturbances of sixteenth-century England: 'Such movements are a proof of blood and sinew and of a high and gallant spirit. . . . Happy the nation whose people has not forgotten how to rebel.'

The mark of the modern world is the imagination of its profiteers and the counter-assertiveness of the oppressed. Exploitation and the refusal to accept exploitation as either inevitable or just constitute the continuing antinomy of the modern era, joined together in a dialectic which has far from reached its climax in the twentieth century."

Source: The Modern World-System, vol. I, p 233.

[En: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Immanuel_Wallerstein]

Strength Index

Country (Strength Index)

United States of America (363)

Germany (355)

France (206)

Italy (203)

United Kingdom (201)

Japan (190)

China (119)

Netherlands (117)

Russian Federation (64)

Spain (62 )

[ Ver: Piana, Valentino (2004).: Hierarchy Structures in World Trade. Economice Web Institute. En:

http://www.economicswebinstitute.org/essays/tradehierarchy.htm ]

Wallerstein

Wallerstein, por sus criticas contra el capitalismo y su postura a favor de los paises “periféricos”, es uno de los ídolos del movimiento anti-globalización.

En la siguiente cita de Wallerstein, sobre el desarrollo de la economía desde la Edad Moderna, se puede notar el tono y el lenguaje cargado de adjetivos que recuerdan a las obras divulgativas de Noam Chomsky.

“In the sixteenth century, Europe was like a bucking bronco. The attempt of some groups to establish a world-economy based on a particular division of labor, to create national states in the core areas as politico-economic guarantors of this system, and to get the workers to pay not only the profits but the costs of maintaining the system was not easy. It was to Europe's credit that it was done, since without the thrust of the sixteenth century the modern world would not have been born and, for all its cruelties, it is better that it was born than that it had not been.

It is also to Europe's credit that it was not easy, and particularly that it was not easy because the people who paid the short-run costs screamed lustily at the unfairness of it all. The peasants and workers in Poland and England and Brazil and Mexico were all rambunctious in their various ways. As R. H. Tawney says of the agrarian disturbances of sixteenth-century England: 'Such movements are a proof of blood and sinew and of a high and gallant spirit. . . . Happy the nation whose people has not forgotten how to rebel.'

The mark of the modern world is the imagination of its profiteers and the counter-assertiveness of the oppressed. Exploitation and the refusal to accept exploitation as either inevitable or just constitute the continuing antinomy of the modern era, joined together in a dialectic which has far from reached its climax in the twentieth century."

Source: The Modern World-System, vol. I, p 233.

[En: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Immanuel_Wallerstein]

0 Comments:

Publicar un comentario

<< Home